Program Notes

kamran ince

The music of Turkish/American composer Kamran Ince bridges Anatolia and the Balkans with the West. The energy and rawness of Turkish and Balkan folk music, the spirituality of Byzantium and Ottoman court music, the tradition of European art music, and the extravert and popular qualities of the American psyche are the base of his sound world. These ingredients happily breathe in cohesion, and they spin the linear and vertical contrasts so essential to his music forward.

Hailed by the Los Angeles Times as “that rare composer able to sound connected with modern music, and yet still seem exotic,” Ince was born in Montana in 1960 to American and Turkish parents. He holds a Doctorate from Eastman School of Music, and currently serves as Professor of Composition at University of Memphis and at MIAM, Istanbul Technical University. His numerous prizes include the Prix de Rome, the Guggenheim Fellowship, the Lili Boulanger Prize, and the Arts and Letters Award in Music from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. His Waves of Talya was named one of the best chamber works of the 20th Century by a living composer in the Chamber Music magazine.

Leading orchestras throughout the world perform his works. Concerts devoted to his music have recently been heard at the Holland Festival, CBC Encounter Series (Toronto), the Istanbul International Music Festival, and Estoril Festival (Lisbon). His music is published by Schott Music Corporation.

His latest projects include Songs With Other Words (2014) (recomposing of selected movements from Mendelssohn’s Songs Without Words) for Spark and Schleswig-Holstein Festival; Abandoned (2014), a dramatic work (mini opera) for Opera Memphis’ Ghosts of Crosstown Project; Fortuna Sepio Nos (2013), a piano trio for Arkas Trio; it’s a nasreddin (2012) for Berlin Counterpoint and Istanbul Festival; Zamboturfidir (2012) for Yurodny (Dublin) and Hezarfen (Istanbul); Symphony in Blue (2012) for Istanbul Modern Museum; Still, Flow, Surge (2011) for Present Music’s 30th anniversary; Far Variations (2009) for Los Angeles Piano Quartet; Concerto for Orchestra, Turkish Instruments and Voices (2009) for the Turkish Ministry of Culture; Dreamlines (2008) to celebrate the 100th Anniversary of Turkish Chamber of Architects (2008); Music for a Lost Earth (ambient music project) (2007); Gloria (Everywhere) (2007) for the Chanticleer Mass project; Turquoise (2005), a project of his various works arranged by him for the Netherlands Blazers Ensemble; and 5th Symphony Galatasaray (2005) in honor of the infamous soccer club’s centennial celebrations.

Five Naxos CD’s of Ince’s music have recently been released. They are Kamran Ince, Music for a Lost Earth, Galatasaray, Hammers & Whistlers, and Constantinople. His other CD’s include In White on Innova, Fall of Constantinople on Decca and Kamran Ince & Friends on Troy.

Ince’s Judgment of Midas, an opera in two acts, commissioned by Crawford Greenewalt to mark the 50th anniversary of Sardis/Lydia excavations, had its concert version premiere in April 2013 in Milwaukee with Present Music and Milwaukee Opera Theatre with Ince conducting.

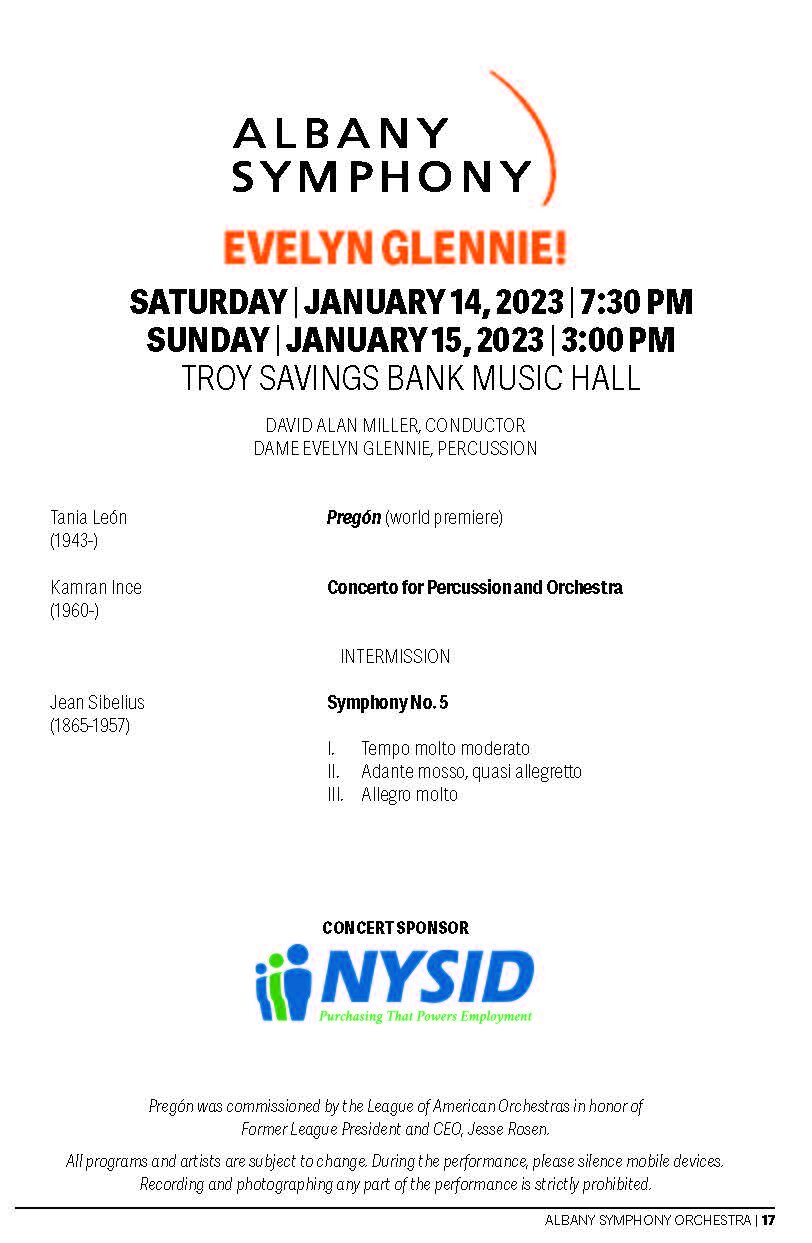

Concerto for Percussion and Orchestra

FROM THE COMPOSER

“As a child growing up in Ankara, I was always fascinated with the Cikirikcilar Hill, an area in Ankara where there are many shops left and right of the pedestrian hill selling cloths, spices, copper pots and pans, household goods (both new and antique), woodwork, beds, and jewelry—and everything else in between. You can usually find anything you are looking for, or not looking for. I suppose it is the old version of a shopping mall, a place that has not really changed with time. The crowds are non-stop, the sounds vary constantly and are always fascinating. In addition to my interest in the sounds of the area, I have always been very fond of the way the word Cikirikcilar itself sounds, a percussive, amusing, unique sound.

All the various sounds and moods of Cikirikcilar Hill and Turkey’s history, with all their various percussive instruments, are the biggest inspiration for this work. Among the numerous percussion instruments I use in the concerto are mostly those that remain unique to Turkey, such as Davul (a small bass drum played on both sides) and Darbuka (an instrument placed between the legs and played with the hands). There are five movements that concentrate on certain sounds in general: The first uses Davul and metals; the second uses skins and some metals; the third uses Darbuka and metals; the fourth uses cymbals with some usage of the new instrument Aluphone (Glennie concert); and the fifth uses Marimba and Davul again.

EVELYN GLENNIE

Dame Evelyn Glennie is the first person in history to create and sustain a full-time career as a solo percussionist, performing worldwide with the greatest orchestras and artists. Glennie paved the way for orchestras globally to feature percussion concerti when she played the first percussion concerto in the history of the Proms at the Royal Albert Hall in 1992.

A leading commissioner of new works, Glennie has commissioned more than 200 works from many of the world’s most eminent composers. “It’s important that I continue to commission and collaborate with a diverse range of composers whilst recognising the young talent coming through," she says Glennie composes music for film, television, theatre, and music library companies. She is a double GRAMMY award winner and BAFTA nominee. She regularly provides masterclasses and consultations to inspire the next generation of musicians.

Leading 1,000 drummers, Glennie had a prominent role in the Opening Ceremony of the London 2012 Olympic Games, which also featured a new instrument, the Glennie Concert Aluphone. “Playing at an event like that was proof that music really affects all of us," she says, "connecting us in ways that the spoken word cannot.”

Glennie's solo recordings currently exceed 40 CDs. These range from original improvisations, collaborations, percussion concerti and ground-breaking modern solo percussion projects.

Glennie was awarded an OBE in 1993 and now has more than 100 international awards to date, including the Polar Music Prize and the Companion of Honour. She was appointed as the first female President of Help Musicians, only the third person to hold the title since Sir Edward Elgar and Sir Peter Maxwell Davies. Since 2021 she has been Chancellor of Robert Gordon University in, Aberdeen, Scotland.

The Evelyn Glennie Podcast was launched in 2020 featuring popular personalities from the world of music, sport, television and academia. Glennie is curator of The Evelyn Glennie Collection, which includes more than 3,500 percussion instruments. The film Touch the Sound, her TED Talk, and her book Listen World! are key testimonies to her unique and innovative approach to sound-creation. Through her mission to "Teach the World to Listen" she aims to improve communication and social cohesion by encouraging everyone to discover new ways of listening in order to inspire, to create, to engage, and to empower.

Bio courtesy of evelyn.co.uk

HARRIET STEINKE

Harriet Steinke is an American composer from Detroit, Michigan. Her music has been described as “a sonorous space of tender moodiness and a patient disquiet” (pianist Lisa Moore) as well as “the antidote to those who say all new music is about struggle and strife, fearful of expression and especially of tenderness” (composer Piers Hellawell). She has received composition fellowships from the Norfolk and Tanglewood summer festivals and she earned undergraduate degrees in english and music at Butler University where her primary mentor was the composer Michael Schelle. She is currently in her third year of graduate studies at the Yale School of Music where her mentors are composers Chris Theofanidis, Aaron Jay Kernis, Martin Bresnick, and David Lang.

FROM THE COMPOSER

Harrietlehre gets its name, in part, from the composer John Adams's orchestral work Harmonielehre, a work I deeply admire. Adams’s work, which gets its name from Schoenberg’s music theory textbook of the same title, translates from German to “study of harmony.” In the same way, Harrietlehre might translate to “study of Harriet.” Having never before written for a full orchestra, I made a long list of different orchestral textures and processes I wanted to explore in my first orchestra piece. The music itself began as a few small ideas that, when combined, resulted in a 7-measure phrase. Harrietlehre is, more or less, 24 (studious) repetitions of that same 7-measure phrase.

JEAN SIBELIUS

The career of Jean Sibelius (1865-1957) was curious. Despite the fact that he lived longer than, say, Camille Saint-Saëns and Richard Strauss, both of whom survived into their 80s, he did not continue composing music until the end, as they did. For the last 30 years of his life, he did not write music “of any stature,” as one biographer put it. He preferred, instead, to live quietly, reflecting on his career and talking to people who came to interview him or pay him homage.

What he did leave, however, is weighty and permanent. His earliest works, such as the Kullervo Suite, En Saga, and the Karelia Suite, celebrate Finland; and certainly his most famous piece, Finlandia, reveals this national pride. But the seven symphonies and Concerto for Violin and Orchestra he composed between 1899 and 1924 made him a composer of international stature.

Symphony No. 5

Premiered in 1915 on Sibelius’s 50th birthday, this symphony—despite its positive reception—underwent two revisions, in 1916 and 1919. It’s the 1919 version in three, not the original four, movements that finally satisfied the composer.

In September 1914 Sibelius wrote, “I am already beginning to glimpse the mountains to which I shall ascend. God opens his door for a moment, and his orchestra is playing the Fifth Symphony.”

A bold statement, that! But the symphony does begin in some otherworldly place, I’d say. The first minutes belong to the brass and winds, sometimes in conversation, but what about? The strings enter, pushing the momentum. Little dotted motives emerge, sometimes just a few cramped notes up and down the scale. A haunting bassoon solo over rustling strings (the strings rustle quite a bit in this symphony) does not soar. It’s not until nine-plus minutes in that everything gels.

Sibelius switches up the feeling of the movement by including a scherzo, which originally was its own movement. Lively wind playing over the strings is, in fact, a sped-up version of the licks we heard at the beginning. Indeed, wherever we listen, we hear music that we’ve heard before, now at a pell-mell pace.

Question: Is the form of this movement sonata-allegro? Do we hear exposition, two themes, development, recapitulation, and coda? Scholars argue yes and no, with the naysayers speaking more about Sibelius’s interest in developing his small-scale motives at will, not by prescription. His music blossoms with its own logic, and it’s up to the listener to hear/feel his organizing principles.

The second movement, however, is a somewhat familiar theme and variations, with the melody heard first in the flute and the pizzicato strings. The tune itself is merry enough, but some of the undercurrent features abrasive seconds and droning pedal points. Throughout you will hear Sibelius’s mastery in tempo, modal, and instrumental changes.

The finale features the restless strings again, a kind of shapeless foreshadowing of the “big tune” that appears next (and then, later, brings the entire symphony to a thrilling close). This melody, announced in thirds in the horns, was said to be inspired by Sibelius’s seeing 16 swans suddenly take off, honking, and if you, too, feel and hear such a moment, you’re in sync. While this is happening, the winds are singing out a lovely melody in E-flat, based on just five notes of the E-flat scale.

A lively section featuring clarinets and other winds captures our attention, followed by strings creating a sense of anticipation. Then the clarinets sing out the familiar tune from the beginning of the movement.

Trumpets (brass started this symphony, remember?) set us up for a reprise of the big tune, with all forces on deck, and the piece concludes with a technique Sibelius has not yet used here: silence. How masterful!

Sibelius notes by Paul Lamar